Dependency inference: Pants's special sauce

Unlike earlier build systems, Pants v2 automatically infers your code's internal and external dependencies. And it does this at the file level, so that you get optimal invalidation, caching, and concurrency performance without having to manually create and maintain mountains of BUILD file metadata.

Scalable build systems need to know about the structure and dependencies of your codebase in order to correctly invalidate work, compute cache keys, and apply concurrency. But how do they get this data?

An important distinguishing feature of Pants v2 is its ability to automatically infer your code's internal and external dependencies. This is in contrast to earlier systems, such as Bazel, Buck, and Pants v1, which rely on handwritten metadata provided in BUILD files and checked into the repo alongside the code they describe.

Why did we make this design choice? Read on to find out!

The Adoption Challenge

In the early iterations of the Pants v2 design, we imagined that it would continue to rely on these heavyweight BUILD files that had become almost traditional in the space. But in 2020, as we began working towards the eventual Pants 2.0.0 launch, and started to imagine what widespread adoption would look like, we began to have second thoughts...

Those other systems were primarily designed for and around the use-cases of a single company (Google, Meta, and Twitter, respectively). And when you design for a single organization, you're working in the context of a single adoption process that you tightly control. You can design for a particular codebase structure, refactoring towards it if necessary. Plus, once onboarding is complete, you have a captive user base that isn't free to seek alternatives. So the difficulty of adoption and of ongoing maintenance tend not to be primary influences on the design.

But with Pants v2, we were, fairly uniquely, creating a system to be used by a wide variety of software engineering teams of all manner of sizes, codebase structures and development practices. We wanted Pants v2 to be adopted over and over and over again. And once the system was in use, we wanted it to delight users, not encumber them.

So we took a deep look at what the burdens are in evaluating, adopting and using a system of this sort. And creating and maintaining dependency information in BUILD files stood out as one of the biggest obstacles.

Handwritten BUILD files are a pain

Selecting the right level of granularity for BUILD file dependency metadata is tricky:

File-level data is the most precise, but that creates much larger BUILD files, that are correspondingly more laborious to maintain. So, in practice, handwritten BUILD file "targets" (the sources and destinations of dependencies) typically span an entire directory or package. But then the data is coarser-grained, which leads to more invalidation, fewer cache hits and less concurrency. Plus, coarser granularity makes it harder to model real-world codebase warts, such as dependency tangles and cycles.

And once you select a level of granularity, it's hard to change: if you split or unify targets, you have to update every single reference to the original targets in any dependent BUILD files.

Now, assuming you've chosen an appropriate level of granularity, every time you add an import statement in a file, you annoyingly have to go and add some corresponding - and redundant! - dependency metadata in a BUILD file. And removing an import statement can be even more laborious: before removing the corresponding dependency from the BUILD file you first have to check that some other file in the same target isn't also importing that dependency. This is a hassle! So, in practice, dependencies are not always added or removed when they should be, and inconsistencies build up over time.

The burden of BUILD file maintenance is widely acknowedged as a barrier to adoption of these sorts of build systems. For example, a recent Bazel community talk reiterated that:

Developers don't want to maintain BUILD files every single time that they edit a change or add a new dependency. These are all overhead that's stopping people from adopting Bazel today. It's just a lot more work that they have to do on top of their normal development workflow, and this extra work slows them down. So adopting Bazel slows down your developer productivity.

And although we were just as guilty of this in Pants v1, it always struck us as a little absurd, because all the dependency information that bloats those BUILD files is already available in the source files themselves, in the form of import statements! It quickly became clear to us that Pants v2 should grab these dependencies via static analysis of your code, instead of you having to manually provide them in BUILD files.

Auto-generating BUILD files

The first approach we considered was to use dependency inference to generate and update BUILD files, but continue to check those files into the repo. This is the path taken by the Gazelle tool for Bazel.

However this approach still has some major drawbacks, as acknowledged by this this upcoming BazelCon talk:

Developers often have to laboriously enumerate dependencies in their BUILD files, which is toilsome and a major source of friction.

For one thing, many BUILD files cannot be completely generated. They still need to be manually edited, both to tweak the generated dependencies and to add any other, non-inferrable metadata. Having an automatic process modify human-edited files, and vice versa, gets messy quickly. How do you customize and correct the generator's output? How do you ensure that human edits aren't erased or overwritten?

Generated BUILD files may be even more verbose than handwritten ones, which bloats pull requests. And they still suffer from the granularity issue: A generator can easily create dependency metadata at the fine-grained file level, which is best for invalidation, cache and concurrency performance, but then any manual metadata, such as setting a resolve, has to be applied at that same granular level, which adds even more verbose boilerplate. So, again, in practice a coarser granularity is usually applied, which harms performance.

What we want, in practice, is very fine-grained dependency metadata, but coarse-grained metadata of other kinds. So we ended up rejecting BUILD file generation as the simplifying mechanism for dependency management.

Pants does do a bit of simple BUILD file generation, using the built-in tailor goal, to streamline onboarding. But these BUILD files are perfunctory and tiny, and notably don't contain dependencies!

Dependency inference

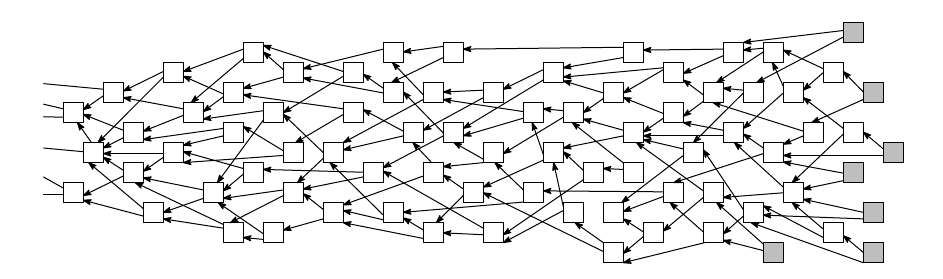

The alternative we landed on was dependency inference: Pants performs the static analysis at runtime, as needed, and uses the data on the fly. Dependency information doesn't - usually - live in BUILD files at all.

This allows you to have very small, simple BUILD files, often just 1-3 lines. These exist to denote code that Pants should operate on, and as a location for you to provide custom metadata (e.g., to specify a test timeout, or a named resolve).

Dependency inference happens at the file level, so is very fine-grained, to support optimal invalidation, cache and concurrency performance. But manual metadata can conveniently be applied at a much coarser grain, leading to a "best of both worlds" situation.

In fact, thanks to new features like target generators, parametrization, and subtree defaults, we are on the way to allowing you to have a lot fewer BUILD files, sometimes even just one for an entire source tree! But, thanks to inference, your dependencies are still modeled at the per-file level.

You can read more about the details and advantages of dependency inference in this post.

Detecting dependencies

So, how does Pants's dependency inference work?

There are two main steps:

- Examine source files to see which symbols they import and which symbols they provide

- Create a mapping from each symbol to the file that provides it

With this mapping in place, it's straightforward to map a file's imported symbols to the files that provide those symbols. And this work is cached on disk and memoized in the Pants daemon's memory, so repeated incremental updates are very fast.

As you can imagine, most of this has to be implemented per-language, e.g. for Python, Java, Scala, Kotlin, Go, Shell and so on, as it requires understanding each language's import/export syntax and semantics (see here for more details about the implementation of dependency inference for JVM languages). And, in fact, we implement dependency inference not just for programming languages but also for frameworks!

For example, the Docker backend can map images referenced in a Dockerfile (e.g., in FROM statements) back to the Dockerfiles that created those images. And the Protocol Buffer backend can map a dependency between .proto files into the corresponding dependency between the source files generated from them!

In fact, we even have support for detecting dynamic dependencies, where code is loaded at runtime via a string. For example, you can optionally have Pants consider literal strings that "look like" Python module or class names (such as foo.bar.baz, or foo.bar.baz.Baz) as "soft imports". This is useful for cases such as Django apps, where the settings.py file references many other external and internal dependencies via strings, rather than import statements.

And if your code has custom dependency inference needs, such as dynamic dependencies named in config files, you can always write a plugin to extend the dep inference logic to your liking.

And if all else fails...

Sometimes, despite all our best efforts, and your customizations, there is no escaping the need for manual dependency metadata. A common case is a dependency on a data file.

In such cases you can simply add dependencies in your BUILD files, the old-school way. But you only need to add the ones that can't be inferred, to augment dep inference, so this still keeps your BUILD files nice and small. And these handful of manual dependencies can still be at the file level, to preserve the fine granularity:

resources(name="my_data", sources=["my_data.txt"])

python_sources(

dependencies=[":my_data"],

)

In the rare case that you want to prevent pants from inferring a dependency, such as one provided at runtime by some mechanism outside Pants's control, you have two options:

You can negate the dependency in the BUILD file, by preceding it with a !:

python_sources(

dependencies=["!provided/dep.py"],

)

You can add a # pants: no-infer-dep pragma on the import line:

import provided.dep # pants: no-infer-dep

Looking back, and forward

In the exactly two years since we released Pants 2.0.0, dependency inference has come a long way, and has become an important selling point for teams looking for scalable build tooling without the hassle of maintaining huge BUILD files, as exemplified by this case study from IBM. So with hindsight, we're really happy with this design choice.

Dependency inference is one of several features we've implemented that help cut down on BUILD file boilerplate. Others include sensible global defaults for target fields, target generators, parametrization, and subtree defaults.

We'll continue to lean into dependency inference in the future, and find even more ways to reduce and even eliminate BUILD file boilerplate. Our goal is to keep making Pants easier to adopt, use, and customize, while also adding new languages and features, and dependency inference will play a big role in this effort.

If you want to speed up and scale up your builds without the boilerplate, come and talk to us!